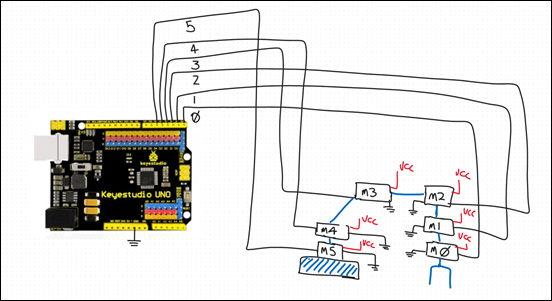

One of the issues I found when powering the servos for the robot arm was that I found I couldn’t power them from the Arduino board, I needed an external power supply. This fact made wiring the servos up challenging as the control signal still had to come from the Arduino but the power elsewhere. Thus, lots of messy wires.

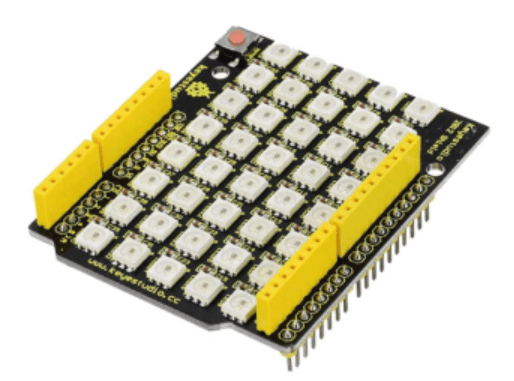

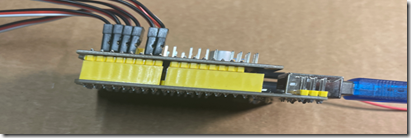

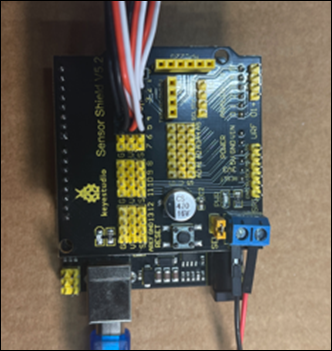

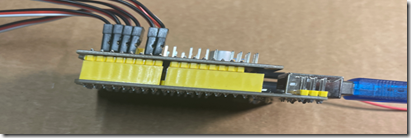

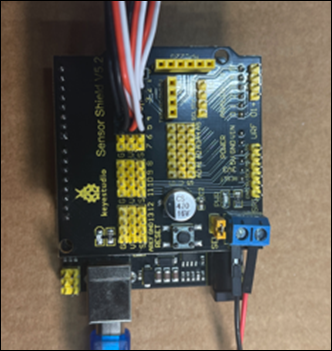

All that has been solved with the addition of a Keyestudio Sensor Shield/Expansion board as seen above.

Basically, the shield simply plugs into the pins in the Arduino controller (extending them) while providing:

– An alternate power supply

– Easy connections for all the servos

A nice compact solution to a few challenges with the robot arm. All I needed to do was connect up the shield onto the Arduino and then connect the servo motors directly to their ports and change nothing else. No code or other wiring was done except to also connect an external power supply to the shield board as seen in the lower right above.

I have to say, that if you need to control devices that require more power than the standard Arduino board can provide then this type of shield is exactly what you want!

Thumbs up to Keyestudio for both the controller:

KEYESTUDIO UNO R3 Development Board For Arduino Official Upgrated Version With Pin Header Interface

and the shield

Keyestudio Sensor Shield/Expansion Board V5 for Arduino

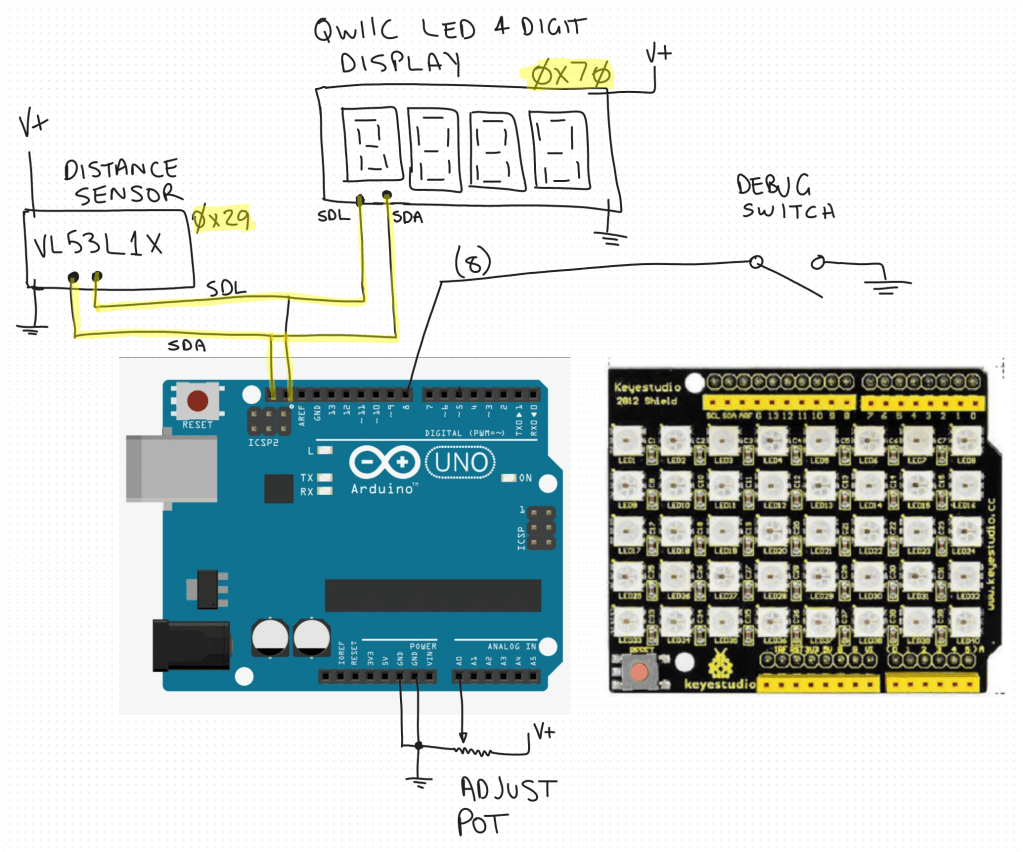

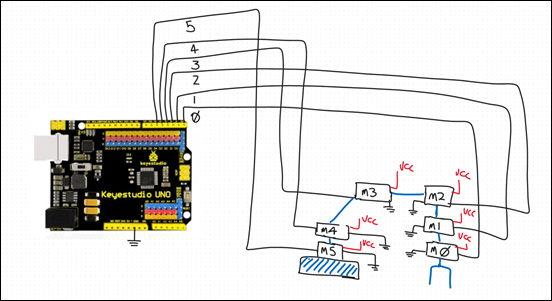

A diagram of the project looks like: